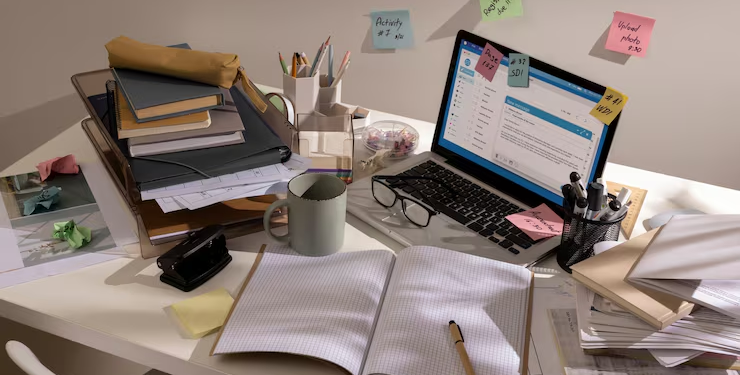

We live in a digital world. We send emails, we sign PDFs, and we store terabytes of data in the cloud. Yet, walk into the back office of almost any law firm, medical practice, logistics company, or manufacturing plant, and you will still see them: stacks of white paper.

The “Paperless Office” was a utopian prediction from the 1970s that never quite came true. While we print fewer casual memos, the documents we do keep—contracts, compliance records, blueprints, and HR files—are critical. And they are heavy.

The problem is that most modern office managers design their spaces based on aesthetics rather than physics. They choose storage units that look sleek in a catalog but are structurally incapable of handling the one thing they are meant to hold. They underestimate the sheer, relentless force of paper weight.

The Physics of the Pulp

To understand why cheap office furniture fails, you have to look at the density of the material. Paper is made of compressed wood pulp. It is dense, dead weight.

A standard ream of 20lb bond paper (500 sheets) is about 2 inches thick and weighs roughly 5 pounds. Now, consider a standard lateral file drawer. It is roughly 30 to 42 inches wide. If you pack that drawer tight with files, you aren’t just storing information; you are storing a geological layer of wood.

A fully loaded 42-inch drawer can easily hold 25 to 30 reams’ worth of paper. That is 150 pounds of static load. That is the equivalent of having an adult human standing inside your drawer, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

If your cabinet has four drawers, and they are all full, you are looking at 600 pounds of mass sitting on a footprint of a few square feet.

The “Sag” and the “Stuck”

This is where the difference between “consumer-grade” and “industrial-grade” becomes painfully obvious.

In cheaper cabinets, the metal gauge is thin. Under the sustained pressure of 600 pounds, the steel frame begins to torque. The bottom of the drawer bows. The tracks—often made of nylon or cheap aluminum—warp under the stress.

The result is the “Stuck Drawer Syndrome.” You pull the handle, but the drawer refuses to budge. Or worse, it slides out halfway and then jams, refusing to go back in. This isn’t just an annoyance; it is a structural failure. The suspension system has surrendered to gravity.

For a file cabinet to actually work, it needs a suspension system that treats 150 pounds like a feather. It requires ball-bearing slides—rows of steel spheres that distribute the weight evenly and allow the drawer to glide effortlessly, even when fully loaded.

The Geometry of the Lateral

The challenge of weight is compounded by the geometry of the “Lateral” file.

Vertical files are deep and narrow. Lateral files are wide and shallow. This design is superior for space efficiency—it doesn’t protrude as far into the room, keeping walkways clear—but it creates a massive leverage problem.

When you pull out a wide, heavy drawer, you are shifting the center of gravity forward by nearly two feet. If the cabinet isn’t engineered with a counterweight or bolted to the wall, that 150-pound drawer becomes a lever that wants to tip the entire unit over onto the user.

This is why the “Interlock System” is the most critical safety feature in your office. A properly engineered industrial cabinet has a mechanical brain inside the lock bar. It physically prevents you from opening more than one drawer at a time. If Drawer A is open, Drawer B is locked shut. This forces the center of gravity to stay within the safe zone.

Cheap cabinets often skip this complex mechanism to save cost, relying on a simple “don’t open two drawers” warning sticker. But physics doesn’t read warning stickers.

The Gauge Game

Ultimately, the durability of your storage comes down to the thickness of the steel, measured in “gauge.” The lower the number, the thicker the steel.

- 24-22 Gauge: This is standard “big box store” metal. It dents if you kick it. It warps under heavy load.

- 20-18 Gauge: This is the commercial standard. It is rigid, robust, and designed for daily abuse.

When you buy a cabinet made of 22-gauge steel, you aren’t buying a permanent asset; you are buying a temporary container. Over time, the static load of the paper will deform the casing, the drawers will misalign, and the lock bars will fail to engage.

Conclusion

It is tempting to treat office storage as an afterthought—to spend the budget on ergonomic chairs and standing desks, and buy whatever cabinets are cheapest.

But storage is infrastructure. It holds the legal and financial history of your company. It needs to be a fortress, not a tin can.

If you are storing gym clothes or empty binders, buy the cheap unit. But if you are storing paper, you need to respect the weight. You need ball-bearing suspension, safety interlocks, and heavy-gauge steel. Whether you are outfitting a law library or a machine shop office, investing in Global Industrial lateral file cabinets ensures that you are fighting the physics of paper with a structure built to win the war against gravity. The paper in your office isn’t going away anytime soon, so you might as well give it a place to live that won’t collapse under the pressure.